More than a mere horse race, the Palio di Siena is a vibrant, living embodiment of medieval history, a complex tapestry of civic pride, rivalry, and unwavering tradition that pulses through the heart of Tuscany. Held twice each year (in 2025, the dates will be July 2 and August 16), this event is not a reenactment; it is a continuation of a centuries-old legacy that defines the very soul of Siena and its people.

For the traveler seeking to understand the authentic spirit of Italy, witnessing the Palio is to step directly into a passionate drama that consumes an entire city. This guide delves into the intricate world of the Palio, offering a detailed exploration of its history, traditions, and the profound significance it holds for the Sienese.

The heart of Siena: a history forged in rivalry and resilience

The story of the Palio is the story of Siena itself, a narrative deeply etched into the city's cobblestones and colored by centuries of independence, conflict, and civic pride. Its origins are not found in a single edict but are woven from a thread of public games, military celebrations, and a fierce desire to maintain a unique cultural identity. While horse races were a common feature in many medieval Italian cities, Siena's Palio evolved into something far more profound.

The earliest precursors to the Palio date back to at least the 13th century. These early contests, known as palii alla lunga, were long-distance horse races run through the city streets, often from outside the walls to the cathedral, celebrating specific religious feasts like the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. However, these were different from the Palio we see today. The modern Palio, the circular race within the confines of the Piazza del Campo, known as the Palio alla tonda, has its direct roots in the 16th century.

A pivotal moment in this evolution was the famous Battle of Montaperti in 1260, where Siena won a stunning victory against its powerful rival, Florence. The celebrations that followed helped to cement the tradition of public games and horse races as central to Sienese civic life. Following the end of the Sienese Republic in 1559 and its absorption into the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, these traditions took on a new, more vital role. The Palio became a symbolic bastion of Sienese identity, a way to preserve the memory of its former glory and the autonomy of its internal districts, the Contrade. Stripped of their political power, the Contrade poured their energy and resources into this competition, transforming it into the primary expression of their sovereignty and pride.

Initially, a variety of races were held in the Campo, some on the backs of buffaloes (bufalate) or donkeys (asinate), which were known for their unpredictability and entertainment value. However, by the 17th century, the horse race had become the definitive event. The first official Palio with horses, organized by the Contrade in the Piazza del Campo as we know it today, is documented as having taken place in 1633. From this point forward, the traditions began to solidify. The decision to hold a second race in August, honoring the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, was added in 1701 at the request of the Oca (Goose) Contrada, which had won the July race and wished to attempt another victory.

The Contrade themselves were not formed for the Palio; they were ancient military and administrative subdivisions of the city. As their military function waned, their social and cultural importance grew, with the Palio becoming their ultimate raison d'être. In 1729, a crucial edict known as the "Bando" issued by Violante Beatrice of Bavaria, the governor of Siena, formally defined the boundaries of the seventeen Contrade, solidifying their number and territories and forbidding mergers or the creation of new ones. This act effectively crystallized the structure of the Palio, preserving the historical districts and ensuring the continuation of their centuries-old rivalries and alliances, which are now a fundamental driver of the event's passionate drama. This deep history is why the Palio is not a historical reenactment; it is an unbroken, living tradition, a vital and visceral connection to a fiercely independent past.

The soul of the city: understanding the 17 contrade of Siena

To comprehend the Palio, one must first understand the Contrade. Siena is divided into seventeen distinct, autonomous districts, or Contrade, each with its own emblem, colors, church, museum, and social club. These are not simply neighborhoods; they are miniature city-states, each with a rich history and a fiercely protected identity. The life of a Sienese is intrinsically linked to their Contrada from birth, with baptisms often taking place at the Contrada's fountain, to death.

What are the Contrade?

The seventeen Contrade are:

- Aquila (Eagle)

- Bruco (Caterpillar)

- Chiocciola (Snail)

- Civetta (Little Owl)

- Drago (Dragon)

- Giraffa (Giraffe)

- Istrice (Crested Porcupine)

- Leocorno (Unicorn)

- Lupa (She-Wolf)

- Nicchio (Seashell)

- Oca (Goose)

- Onda (Wave)

- Pantera (Panther)

- Selva (Forest)

- Tartuca (Tortoise)

- Torre (Tower)

- Valdimontone (Valley of the Ram)

Of these seventeen, only ten participate in each Palio: the seven that did not race in the corresponding Palio of the previous year, plus three drawn by lot from the remaining ten. This system ensures a rotation, heightening the anticipation and the stakes for those chosen to run.

Alliances and rivalries: the social fabric of the Palio

To truly grasp the soul of the Palio, one must look beyond the racetrack and into the intricate, centuries-old web of social diplomacy that governs the relationships between the Contrade. This complex system of official alliances (alleanze) and deeply entrenched rivalries (inimicizie) is the invisible engine that drives the Palio's drama. It transforms the race from a simple competition into a year-round strategic game of power, pride, and historical memory, where every interaction is layered with meaning.

A Contrada’s success in the Palio rarely depends on its horse and jockey alone. Alliances are crucial. An allied Contrada can provide support during the race, with its jockey working to obstruct a common rival rather than focusing solely on their own victory. These relationships are formally recognized and are a source of great pride. When two allied Contrade march in the Historical Parade (Corteo Storico), they exchange flags in a display of solidarity. These alliances are often born from shared histories, geographical proximity, or a mutual opposition to a more powerful Contrada. For instance, the Tartuca (Tortoise) and Chiocciola (Snail) once shared a strong bond against the dominant Oca (Goose). While some alliances are steadfast and have lasted for centuries, others can be fragile, shifting with the changing political landscape within the Palio.

Even more powerful than the alliances, however, are the rivalries. A rivalry in Siena is not a casual sporting dislike; it is a formal state of animosity known as a cuffia. This enmity is so profound that the primary goal of a Contrada often becomes not its own victory, but the defeat of its official enemy. A Palio is considered a success if the rival Contrada loses, even if one does not win. These rivalries are typically born from disputes over territory, insults exchanged centuries ago, or conflicts during a past Palio that were never resolved.

Some of the most famous and bitter rivalries include:

- Torre (Tower) and Oca (Goose): Arguably the most intense and famous rivalry, its origins trace back to the 17th century. Disputes over territory and a series of provocations have fueled this animosity for generations, making any Palio in which both participate a crucible of tension.

- Chiocciola (Snail) and Tartuca (Tortoise): This is one of the oldest rivalries, officially dating to 1910 but with roots in the early 18th century. It began over a territorial dispute and escalated through mutual insults and Palio-related conflicts, ending a once-strong alliance.

- Aquila (Eagle) and Pantera (Panther): A more recent, yet incredibly fierce, rivalry that exploded in 1947 over accusations of race-fixing and heated arguments between the jockeys and members of the Contrade.

- Istrice (Porcupine) and Lupa (She-Wolf): This rivalry is rooted in disputes over territorial boundaries in the early 20th century.

These official enmities are only part of the story. The social fabric is further complicated by unspoken tensions and strategic calculations known as partiti. These are secret, often monetary, deals made between the leaders of the Contrade and the jockeys in the days before the race. A Contrada might pay a jockey from another Contrada to actively hinder its rival, or to clear a path for its own horse. This shadowy world of diplomacy and betrayal adds an electrifying layer of unpredictability to the race. What appears to be a simple move on the track is often the result of a complex bargain struck days earlier. It is this combination of sworn loyalty, historical hatred, and clandestine strategy that makes the Palio a deeply human drama, a passionate and living testament to Siena's unique social identity.

The four days of the Palio: a city in suspense

The Palio is not a single-day event. The city enters a state of heightened excitement and preparation in the four days leading up to the race, a period known as "I Giorni del Palio."

Day 1: The "Tratta" and the assignment of the horses

- The process begins with the Tratta, the selection and assignment of the horses. Ten horses are chosen from a larger pool of candidates by the Capitani (Captains) of the participating Contrade. These are not purebreds, but rather mixed-breed horses, or barberi, selected for their agility and suitability for the tight and dangerous curves of the Piazza del Campo. The assignment is done by lottery, a moment of immense tension and speculation. A powerful horse assigned to a favored Contrada can send ripples of excitement through the city, while a less promising mount can lead to despair.

Days 2 & 3: Trial races and the Cena della prova generale

- Six trial races, or prove, are held in the Piazza del Campo, one in the morning and one in the evening, over the next three days. These trials allow the fantino, or jockey, to familiarize themselves with their horse and the track. While not as intense as the final race, they are crucial for testing the horse's condition and the jockey's strategy.

The evening before the Palio, the fifth trial, the Prova Generale, is held. Following this, each participating Contrada holds a grand open-air dinner, the Cena della Prova Generale. Thousands of contradaioli (members of the Contrada) gather at long tables set up in the streets and piazzas of their district to eat, sing, and support their fantino. This is a powerful and moving display of community and hope.

Day 4: The day of the Palio race

The final day is a meticulously orchestrated series of events, rich with ceremony and tradition.

- Morning: The final trial race, the Provaccia, takes place. It is run with less intensity as no one wants to risk injuring the horse before the main event. Following this, the Archbishop holds a special mass for the fantini in the chapel of the Piazza del Campo.

- Afternoon: The most sacred and moving ritual occurs: the blessing of the horse and jockey. Each horse is led into its Contrada's church, where the priest imparts a blessing, concluding with the famous phrase: "Va' e torna vincitore!" ("Go, and return victorious!").

- The Corteo Storico: Before the race, the magnificent Corteo Storico, a historical parade, takes place. Over 600 participants in splendid medieval costumes representing all seventeen Contrade, as well as institutions of the ancient Republic of Siena, march through the Piazza del Campo. This is a stunning spectacle of flag-waving, drumming, and historical pageantry that celebrates Siena's glorious past.

- The Race: Finally, as evening approaches, the climax arrives. The jockeys, riding bareback, emerge into the Piazza del Campo. The start of the Palio is a complex and often lengthy process. The Mossa, the starting line, is formed by two ropes. Nine of the ten horses enter the space between the ropes in an order determined by lot. The tenth horse, the rincorsa, remains outside. The race begins only when the rincorsa decides to enter the starting area at a gallop. This can take minutes or even over an hour, creating an atmosphere of almost unbearable tension.

The race itself is a frantic, chaotic, and thrilling spectacle, consisting of three laps of the Piazza del Campo. It is a no-holds-barred contest; jockeys are permitted to use their whips (nerbi, made of stretched, dried bull's penis) not only to spur their own horse but also to hinder their opponents. A horse can win without its rider; if a horse crosses the finish line first, even without its fantino, it is declared the winner for its Contrada. The race is over in about 90 seconds, but for the Sienese, those moments are an eternity.

The Siena horse race: rules, thrills and a 90-seconds climax

The Mossa: a tension-filled start

The moments before the Palio begins are among the most emotionally charged in the entire event. The start, known as the Mossa, is not a simple "ready, set, go." It is a complex and nerve-wracking ritual that can last for an agonizingly long time, building the suspense in the Piazza del Campo to an almost unbearable level.

The starting line is formed by two thick ropes, called canapi, stretched across the track near the Costarella dei Barbieri. The order in which the ten participating horses enter this space is determined by a lottery drawn just moments before. The Mossiere, the official starter, calls out the name of each Contrada. One by one, nine of the ten horses and their jockeys enter the tight space between the two ropes.

The tenth horse, known as the rincorsa (the "run-in"), remains outside. The race officially begins only when the rincorsa decides to enter the area between the canapi at a gallop. This gives the tenth jockey immense strategic power. They can wait for a moment that favors their own Contrada or an allied one, or they can try to start when their rival is in a poor position—blocked by other horses or facing the wrong way.

During this time, the nine horses trapped between the ropes are in a state of chaos. Jockeys shout, horses jostle for a better position, and the crowd watches in tense silence, broken by murmurs and sudden gasps. The Mossiere must try to maintain some semblance of order, and can declare a false start if the alignment is not valid when the rincorsa enters. This entire process can take just a few minutes, or it can drag on for over an hour, with multiple false starts that reset the entire procedure, ratcheting up the tension with every passing moment until the final, explosive start.

How a contrada wins the Palio

While the goal is simple—to be the first to cross the finish line after three laps—the way victory is achieved and defined in the Palio is unique. The race is a whirlwind of raw power and strategy, governed by a few crucial rules.

The winner of the Palio is, quite simply, the horse that crosses the finish line first. Crucially, a horse can win without its jockey. If a fantino is thrown off during the treacherous turns of the track, their horse is declared scosso ("shaken loose"). An unmounted horse is still an active participant in the race. If a cavallo scosso manages to complete the three laps ahead of all the others, it wins the Palio for its Contrada. This has happened more than two dozen times in the history of the event and is considered a perfectly valid and glorious victory.

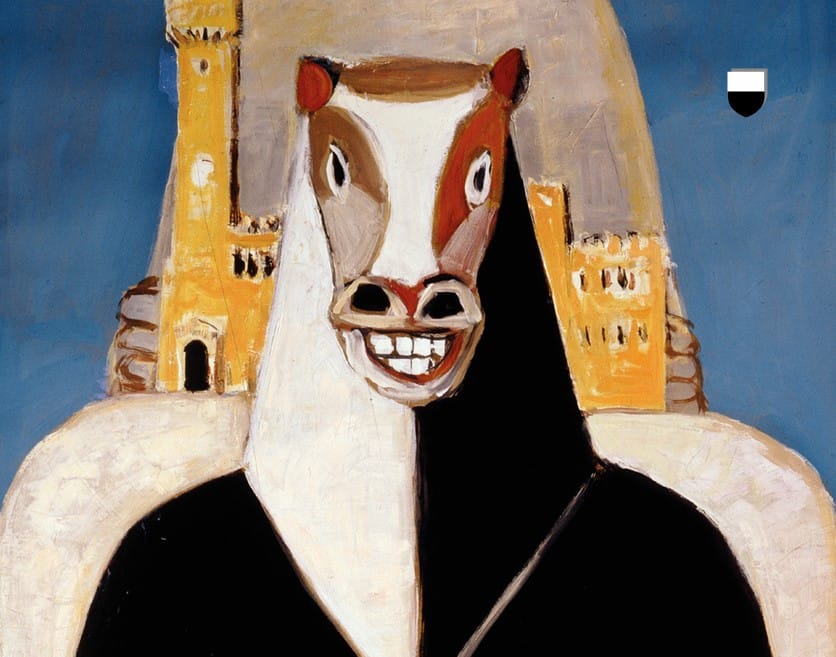

The Drappellone, the painted silk banner, is the only prize. There is no monetary reward for the winning Contrada, only the immense honor and glory of possessing the banner. The moment the winner is confirmed, the members of the victorious Contrada erupt onto the track in a wave of jubilation. They seize the Drappellone, which becomes a sacred relic, and begin a celebration that will last for weeks, if not months. The winning horse and jockey are treated as heroes, their names immortalized in the history of their Contrada and the city of Siena itself.

Experiencing the Palio: a practical guide for the curious traveler

Attending the Palio is an intense and unforgettable experience, but it requires planning and an understanding of the local customs.

How to watch the Palio di Siena

- There are several ways to watch the Palio. The center of the Piazza del Campo is free to enter, but it becomes extremely crowded, and standing for several hours in the summer sun is required. It is essential to arrive early in the afternoon. Alternatively, one can purchase tickets for the bleachers set up around the square or for a coveted spot on a balcony of one of the buildings overlooking the Piazza. These are expensive and must be booked far in advance.

Tips for respectful observation

- The Palio is not a tourist show; it is a deeply significant event for the Sienese. Visitors should be respectful of the traditions and the passion of the contradaioli. During the days of the Palio, it is advised not to wear the colors of any Contrada unless you are a member, as this can be seen as provocative.

Beyond the race: immersing yourself in the city

- To truly appreciate the Palio, one should explore the city in the days leading up to the race. Visit the Contrada museums (many are open to visitors by appointment), witness the trial races, and feel the palpable energy building throughout the city. Attending a Cena della Prova Generale can be a highlight, offering a genuine taste of the Contrada spirit, though securing a ticket often requires a local contact or booking through a specialized agency.

More than a race, a reason for being

The Palio di Siena is a paradox. It is at once a celebration of the sacred, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and a raw, sometimes brutal, expression of secular competition. It is a spectacle of immense historical pageantry and a deeply personal, localized affair. To the outsider, it may appear as ninety seconds of beautiful, chaotic frenzy. But to the Sienese, those ninety seconds are the culmination of an entire year—or a lifetime—of planning, hoping, and belonging.

In an increasingly globalized world where local traditions often fade into homogenized folklore, the Palio stands as a defiant monument to the power of cultural identity. It is the social glue that binds the Sienese community, a complex system of belonging that shapes lives from the baptismal font of the Contrada to the funeral rites. It serves as a living lesson in history, strategy, and passion, passed down through generations. To witness the blessing of the horse in its Contrada church, to stand among thousands in the sun-drenched Piazza del Campo feeling the ground tremble, and to see the unadulterated explosion of joy from the victors and the profound, silent grief of the losers is to understand Italy on a level that few travelers ever reach.

The Palio is not designed for tourists; it is something the Sienese do for themselves. And in that authenticity lies its magnetic appeal. It is a raw, unfiltered glimpse into the soul of a city that refuses to let its spirit be tamed. It is a reminder that some traditions are not meant to be simply observed, but to be felt—a powerful, thundering heartbeat that echoes from the medieval past and resounds, with astonishing force, in the present. To have experienced it is to carry a piece of Siena's fierce and beautiful heart forever.

For more information and fascinating facts about the Palio di Siena → visit this official website.

Start here below to plan your visit to Siena, where you can experience the charm of its medieval streets and its iconic square, as well as the art and culture of its museums and galleries.

To learn more about Tuscany → Read this guide, which contains all the information you need to discover the region.